eBPF's ability to reprogram the kernel for networking, observability and security use cases is an incredible super power, however, to start using the technology you must first understand how and where to hook into the Linux kernel. The technology provides the means for tapping into almost any part of the kernel, but this flexibility comes at a cost – applying it to a new area is daunting if you aren't comfortable navigating the Linux source / kernel APIs.

Many eBPF resources available today explore how to write eBPF programs for well known hooks (syscalls, XDP, etc) and leave future application up to the reader. While learning to write a program is half the battle, you can't start writing a program without first knowing where to attach and the data structures available to the attachment point. Therefore choosing the correct probe is crucial for solving novel challenges and can even help avoid complexity and unstable APIs.

In this post, we will explore strategies to inspect the Linux source to write eBPF programs. These tactics will provide the necessary skills for fearlessly navigating Linux and were recently employed to supplement Pixie's protocol traces with a socket's local address (pixie#1989).

Ftrace is a function tracer for Linux. While it has evolved into a suite of tracing utilities, for our purposes it can be thought of as a means for tracing the entry and exit of any function1 within Linux. This dynamic tracing is supported by nop instructions added to the start of every kernel function. When tracing is disabled, these nops are left in place and the kernel remains performant. When tracing is requested, ftrace transforms these nops into instructions that record the function call graph (see the appendix for a talk with more details).

While ftrace's primary interface is through the /sys/kernel/debug/tracing directory, it's often more convenient to use a ftrace frontend such as trace-cmd. Trace-cmd makes it easy to craft one-liners for adhoc tracing, so it's better suited for our use case. The typical workflow consists of recording a trace (trace-cmd record) followed by a command to inspect the trace file (trace-cmd report).

Ftrace provides a wealth of configuration options. For identifying where to add eBPF programs, we won't look into these possibilities, but I recommend checking out the kernel documentation and other ftrace resources for more details.

Pixie is an observability tool for K8s that provides protocol traces (request/response spans) between your microservices. Pixie captures these spans via eBPF hooks on socket syscalls. One of the gaps in this tracing was that the local address of the connection (IP and port) was missing. With this detail in mind, let's explore how ftrace can identify the correct function to probe to capture this information.

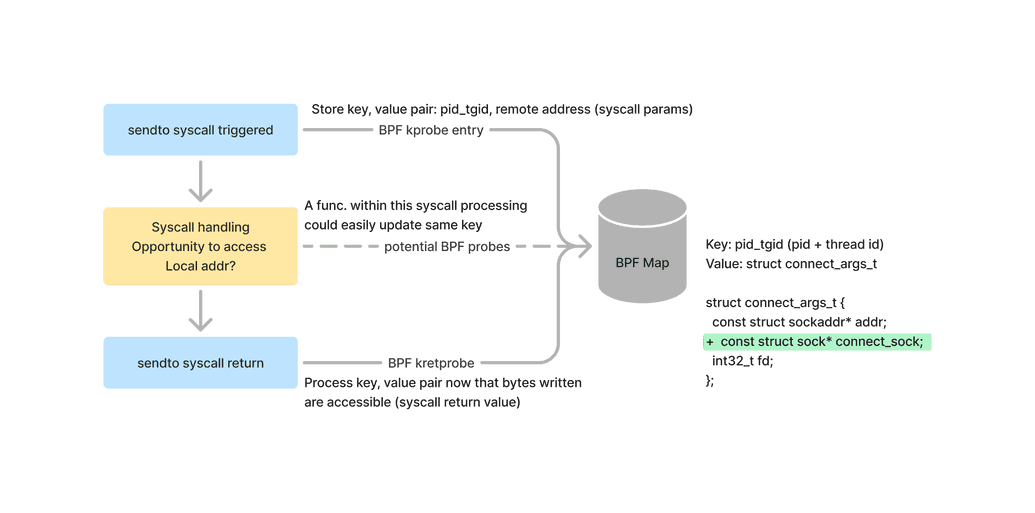

The socket syscall APIs provide easy access to the remote details of a connection. Since eBPF can inspect the arguments of a kernel function, these are readily accessible and how Pixie tracks the remote side of the connection. Unfortunately, the local side of the connection is referenced through the socket file descriptor. There are user space APIs to inspect the fd (getsockname, netlink sock_diag), but there isn't an equivalent interface available to BPF's restricted environment.

ssize_t sendto(int sockfd, const void buf[.len], size_t len, int flags,

const struct sockaddr *dest_addr, socklen_t addrlen);

int connect(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);

ssize_t sendmsg(int sockfd, const struct msghdr *msg, int flags);

# msg->msg_name contains the struct sockaddr

The beginning of the investigation started with running a curl command under ftrace's function graph tracer. This provides all the kernel functions that service this command and are potential candidates for intercepting the local address and port. The following invocation only enables ftrace for the curl command (-F argument), so any kernel handling for other processes is already filtered out.

sudo trace-cmd record -F -p function_graph curl http://google.com

Since the kernel performs many complex operations on our behalf, the resulting trace needs to be filtered to the socket handling. To do this, we need to first filter the traces to the syscalls. They can be identified by searching for any functions with a _x64_sys prefix as seen below:

curl-965264 [003] 856720.850841: funcgraph_entry: | __x64_sys_sendto() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850841: funcgraph_entry: | x64_sys_call() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850841: funcgraph_entry: | __sys_sendto() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850842: funcgraph_entry: | sockfd_lookup_light() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850842: funcgraph_entry: 0.301 us | __fdget();curl-965264 [003] 856720.850843: funcgraph_exit: 0.794 us | }curl-965264 [003] 856720.850843: funcgraph_entry: | security_socket_sendmsg() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850843: funcgraph_entry: | apparmor_socket_sendmsg() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850843: funcgraph_entry: | aa_inet_msg_perm() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850844: funcgraph_entry: | __cond_resched() {curl-965264 [003] 856720.850844: funcgraph_entry: 0.267 us | rcu_all_qs();curl-965264 [003] 856720.850844: funcgraph_exit: 0.736 us | }curl-965264 [003] 856720.850845: funcgraph_exit: 1.276 us | }curl-965264 [003] 856720.850845: funcgraph_exit: 1.793 us | }curl-965264 [003] 856720.850845: funcgraph_exit: 2.326 us | }

From here, we started to investigate the child functions of the socket send syscalls (sendto, sendmsg, sendmmsg). Since these syscalls comprise a complete transmission to the socket, additional state management can be avoided if a child function is probed. For example, it might be possible to capture the local address from the socket syscall, however, this could be complex to implement correctly. Web servers are known to have pre-forking threading models that issue the socket and sendto/sendmsg/sendmmsg syscalls from different threads. While this architecture isn't well known for clients, capturing the data from within a single syscall limits any potential unknowns.

As we uncovered relevant functions, they were cross referenced with https://elixir.bootlin.com/ to identify if a function was viable. An ideal function should have a socket data structure as an argument or return value (interface eBPF can access) and be a stable kernel interface. After looking through a variety of options, tcp_v4_connect and tcp_v6_connect appeared to be the clear winners. These functions' first argument contained a sock struct that contains the local address. From a stability standpoint, these functions were defined within the tcp_prot and tcpv6_prot structs. In C programming, it's common to define an OOP like interface with a struct that contains function pointers – meaning these functions are more likely to be stable than a random kernel function. Checking this function prototype across different kernel versions validated that assumption.

From our past experience working on these socket tracing use cases, we knew that this one function wouldn't be enough. The curl command we inspected creates a new TCP connection, but what about connections that are picked up mid stream (long lived TCP connections)?

Armed with the process for investigating these kernel functions, let's re-apply this to an in flight connection.

To simulate this, netcat was used for the server side and telnet for the client side. Ftrace was attached after telnet was connected to limit tracing to the message sending.

(term1) $ nc -l 8000 -v &(term1) $ telnet localhost 8000Trying 127.0.0.1...Connected to localhost.Escape character is '^]'.(term2) sudo trace-cmd record -P ${pid_of_telnet} -p function_graph# tcp_v4_connect was missed as expected(term2) sudo trace-cmd report | grep tcp_v4_connect(term2) sudo trace-cmd report | grep tcp_sendmsgtelnet-1554313 [004] 1183569.050034: funcgraph_entry: | tcp_sendmsg() {

After reviewing the trace report, the tcp_sendmsg function was identified. This function also exists within the tcp_prot and tcpv6_prot, which bolsters our confidence in its stability. With the new connection and mid stream cases covered, this concluded the investigation for capturing the local address!

20 lines of eBPF code later and Pixie was able to capture the local address of tcp sockets! While the change itself was small, understanding the kernel's TCP state machine and navigating the source with ftrace was crucial for the implementation. We've found ftrace to be an invaluable tool for eBPF programming and recommend that you add it to your toolbelt!

- ftrace: trace your kernel functions! (March 2017, Julia Evans)

- trace-cmd: A front-end for Ftrace (Oct 2010, Steven Rostedt)

- Debugging the kernel using Ftrace - part 1 (Dec 2009, Steven Rostedt)

- Debugging the kernel using Ftrace - part 2 (Dec 2009, Steven Rostedt)

- Kernel documentation

Understanding the Linux kernel via Ftrace - (2017, Steven Rostedt)

Footnotes

- Inline functions won't show up in this tracing. In these cases, the closest non-inlined parent function could be used.↩

Terms of Service|Privacy Policy

We are a Cloud Native Computing Foundation sandbox project.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.

Copyright © 2018 - The Pixie Authors. All Rights Reserved. | Content distributed under CC BY 4.0.

The Linux Foundation has registered trademarks and uses trademarks. For a list of trademarks of The Linux Foundation, please see our Trademark Usage Page.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.